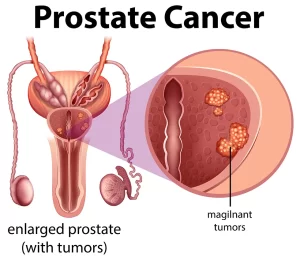

Carcinoma of the prostate stages, causes, treatment and How treatable is prostate cancer?

Carcinoma of the prostate, also most commonly referred to as prostate cancer, is a type of cancer that develops in the prostate gland. The prostate gland is a small, walnut-shaped gland in the male reproductive system that sits below the bladder and in front of the rectum.

Carcinoma of the prostate

Early diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer can greatly improve the chances of a successful outcome. Treatment for prostate cancer depends on many factors, including the stage of the cancer, the man’s age and overall health, and his preferences.

Age Incidence

Rare before the age of 50. The incidence then increases with an increase in age to reach a peak incidence in the 9th decade of life (in the nineties). Common in the USA & Europe (dietary factors).

Risk factors

- Age.

- Ethnicity.

- Genetic.

- Family history.

Pathology

- Adenocarcinoma from the columnar epithelium of the prostatic acini (commonest). It occurs in the peripheral zone of the prostate that is located posterior to the ejaculatory ducts.

- Transitional carcinoma from the transitional epithelium lining the prostatic ducts (rare) occurs around the prostatic urethra in the central and transition- zones.

Grading (Gleason Score)

The Gleason score is based on the degree of glandular differentiation of the tumor. Glandular differentiation ranges from grade 1 (well differentiated) to grade 5 (poor differentiated). Since the patterns of differentiation in a single tumor are usually variable, the 2 most prominent grading patterns in a single tumor are selected by the pathologist. They are added together to give the Gleason score:

- Well-differentiated tumor: Gleason 2-4

- Moderately differentiated tumor: Gleason 5-7

- Poorly differentiated tumor: Gleason 8-10

E.g. if the 2 most prominent grading patterns in a single tumor are grades 2 and 4, the Gleason score would be 2 + 4 = 6 (moderately differentiated tumor).

Clinical Picture:

1. A small tumor (good prognosis) is asymptomatic. It is suspected in the presence of:

- a hard nodule felt by digital rectal examination (DRE); or.

- ↑ serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA). A prostatic biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis.

2. A large tumor (bad prognosis) causes one or more of the following manifestations:

- Obstructive urinary symptoms and hematuria from malignant infiltration of the prostatic urethra.

- Anuria from malignant infiltration and complete obstruction of both ureters behind the bladder.

- Bone pain from bone metastasis.

Investigations

- Increased serum prostate specific antigen (PSA): it is not specific for prostatic carcinoma. It is also increased in the presence of prostatitis and BPH (normal serum PSA level = 0-4 ng/ml).

- DRE: identification of hard nodule or asymmetry of both lobes.

- Trans-rectal ultrasound: a hypoechoic lesion in the prostate, usually in the peripheral zone.

- Trans-rectal ultrasound guided biopsy from a suspicious prostatic hypoechoic lesion or a clinically felt hard nodule by DRF.

- CT abdomen & pelvis. Best for lymph node status.

- MRI. Best for local status of the tumor.

- Bone scan. For identification of bone metastasis.

Metastasis

- Hematogenous spread to the bone (lumbar vertebrae, pelvic bones, femur), lungs, liver, and brain. Bone metastasis is commonly osteoblastic. Osteolytic metastasis occurs rarely.

- Lymphatic spread to the pelvic (iliac and obturator) lymph nodes.

- Direct spread to the bladder, seminal vesicles or lower end of the ureters. Both ureters are sometimes completed obstructed by metastatic spread with subsequent anuria. The tumor does not reach the rectum because of Denonvillier’s fascia which acts as a natural barrier (it is a tough fibromuscular layer present between the prostate and rectum).

Treatment

- Active surveillance: small asymptomatic tumors do not necessarily progress to bigger sizes and higher grades, especially in patients older than 70 years. Follow up biopsy is advised.

- Radical prostatectomy: for small well-differentiated tumors with signs of progression during expectant treatment, or moderately differentiated tumors. The prostate, seminal vesicles and pelvic (iliac and obturator) lymph nodes are removed. The membranous urethra is then anastomosed to the bladder neck. Complications: impotence and urinary incontinence. postatectomy could be done by open approach, laparoscopic or robotic assisted.

- Radiotherapy: for both curative palliative intents. Complications: radiation cystitis, impotence and vesico-rectal fistula.

- Hormonal treatment: advanced and metastatic carcinoma of the prostate: Androgen deprivation: can be achieved by: (i) bilateral orchiectomy; (ii) anti-androgens as flutamide and cyproterone acetate; (iii) diethyl stilbestrol; or (iv) LHRH agonists. (v) LHRH antagonists.

- Palliative treatment: Transurethral resection of malignant prostatic tissue in acute retention of urine from invasion of the prostatic urethra. Ureteric stenting in hydroureteronephrosis.

You can subscribe to Science online on YouTube from this link: Science Online

You can download Science Online application on Google Play from this link: Science Online Apps on Google Play

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), TRUS biopsy, Prostate disease symptoms and treatment

Enlarged prostate symptoms, Prostatic artery embolization (PAE) importance and risks

Prostate function, structure, lobes, Benign enlargement of prostate and malignant prostatic tumor

Nephroblastoma (Wilm’s tumor), Risk factors of Urothelial tumors (Tumors of transitional epithelium)

Urinary bladder structure, function, Control of micturition by Brain and Voluntary micturition

Urinary system structure, function, anatomy, organs, Blood supply and Importance of renal fascia

Histological structure of kidneys, Uriniferous tubules & Types of nephrons