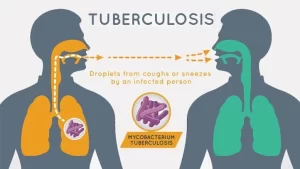

Tuberculosis symptoms, What causes TB disease? and Can TB be transmitted through saliva?

Tuberculosis is a chronic bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis leading to the formation of caseating granuloma with central caseation surrounded by epithelioid cells and Langerhans giant cells followed by an outer layer of lymphocytes and fibrous tissue.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by aerobic bacilli which when stained resist decolorization by strong acids and so-called acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in the direct smear stained by the “Ziehl-Neelsen method” The AFB takes red color against the blue background. It is transmitted through droplets, however, less than 1% is attributed to bovine mycobacterium (Mycobacterium bovis) where infection occurs through ingestion of infected milk.

Spectrum of the infection

Tuberculous infection presents as Primary TB or Post-Primary TB.

1. Primary TB (The Primary Complex)

- Comprises the reaction at the site of the initial infection (lung-tonsil intestine), together with that which develops in the regional lymph nodes.

- Primary TB of the lung consists of a parenchymal component and a glandular component in the form of hilar lymphadenopathy with the lymphatics connecting both lesions.

- This develops within 4-6 weeks of the first (primary) infection and its progress is limited and there are few if any, symptoms. Such parenchymal component is usually peripherally located at the lower part of the upper lobe or the upper part of the lower lobe. The fate of primary TB is either healing or development of post-primary ТВ.

- Healing usually takes place. The tuberculin test becomes positive after 4-6 weeks. from the primary infection, denoting the development of cell-mediated immunity (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) to tubercle bacilli. The lymph nodes of the primary tb subside and the peripheral lung lesion becomes reduced to a small nodule or they may calcify and become evident on the chest x-ray indefinitely (Ghon’s focus) denoting complete healing of primary TB.

- However, healing may be incomplete and the AFB is still viable at the site of primary TB of the lung for a long period. Reactivation of this incompletely healed primary TB is one of the sources of post-primary TB.

2. Post-primary TB

Post-primary TB (Secondary TB) refers to any development of TB lesion beyond the first 4-6 weeks of the primary infection i.e. after the development of tuberculin hypersensitivity.

Its fate is usually:

1. Healing (partial or complete)

2. Development of allergic reaction which occurs after 4-6 weeks, that is when tuberculin skin test (TST) becomes positive. At this point, TB infection can either progress to active TB infection (post-primary TB), or remain silent (latent TB), but has the potential to reactivate later on.

Allergic reactions may occur secondary to exposure to the foreign protein of the AFB (tuberculoprotein). Such allergic reactions may be manifested in different forms such as the development of tuberculin hyper-sensitivity (tuberculin test becomes positive), erythema nodosum, phlectinular conjunctivitis, pleural effusion, and epituberculosis.

The latter occurs from the development of allergic reactions around the parenchymal as well as the glandular components of the primary TB. Such enlarged hilar lymph nodes especially in children, may compress a bronchus causing an atelectasis reaction developing around the parenchymal component of the primary TB may appear as a transient diffuse area of radiological hazy opacification (exudative lesion) and hence it is sometimes referred to as “benign exudative reaction”.

3. Spread:

The Spread of primary TB in the lung leads to post-primary tuberculosis. Spread of primary TB of the lung may occur by several routes:

A. Bronchial Spread

Bronchial Spread leading to “bronchogenic pulmonary TB” : this results in TB pneumonia, TB bronchopneumonia, nodular infiltration, cavities surrounded by small nodules, fibrocavitary TB or TB lesions may be confined to the bronchial tree. This condition is known as endobronchial TB.

B. Lymphatic spread (lymph-borne TB)

This leads to mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Enlargement of lymph Nodes around the middle lobe bronchus in children has a special importance Extrinsic bronchial compression decreases the caliber of the middle lobe bronchus resulting in repeated bronchial infection i.e. Obstructive pneumonitis and is called middle lobe syndrome. If the bronchial obstruction persists, the lobe becomes atelectatic then permanent damage in the form of bronchiectasis occurs. It should be noted that the lymph drains ultimately in the bloodstream. Accordingly, the fate of TB lymphatic spread can be ultimately similar to that caused by hematogenous TB.

C. Hematogenous TB (blood steam spread)

This may occur either in an acute form or a chronic form.

- Acute hematogenous TB in the lung is manifested as acute miliary TB.

- Other organs may also be affected especially the meninges in children resulting in TB meningitis. Dissemination all over the body results in TB septicemia or typhoid-like TB (hyper-acute TB).

- On the other hand, hematogenous dissemination may occur in a chronic form. The AFB remains dormant for a long time, and then reactivation occurs and causes organ TB.

Clinical Picture

Symptoms:

- TB may be accidentally discovered during radiological examination despite the absence of symptoms.

- Common chest symptoms are cough (dry or with expectoration) hemoptysis or chest pain. Exertional dyspnea can occur secondary to massive pleural effusion, tension pneumothorax, atelectasis, or chronic miliary TB causing interstitial fibrosis.

- TB can also be present by night fever, sweating, anorexia, loss of weight, lassitude, easy fatigability, frequent colds, or even amenorrhea in females.

- Concurrent systemic involvement by TB may be another manifestation of extrapulmonary TB.

Signs:

Almost any combination of physical signs may be found e.g. consolidation, atelectasis, effusion, fibrosis, or pneumothorax. On the other hand, the signs may be slight e.g. apical crepitations.

Attention should be paid to manifestations of extrapulmonary dissemination (organ TB) and for any TB complications e.g. amyloidosis (nephrotic syndrome), suprarenal affection, aspergilloma in a tuberculous cavity, TB empyema or pyopnumothorax from ruptured TB cavity, cor pulmonal, malignancy (scar carcinoma), pericardial effusion, polyserositis, and respiratory insufficiency.

Clubbing do not occur in pulmonary TB except if complicated by TB bronchiectasis, TB empyema, or interstitial fibrosis. Lower limb oedema in TB may be related to hypoproteinemia in TB bronchiectasis or nephrotic syndrome in the amyloid kidney or right heart failure from extensive TB.

Differential Diagnosis

Because of the wide range of symptoms and signs of pulmonary TB, it can be included in the differential diagnosis of most respiratory diseases. Mycobacterium (M) TB should be differentiated from infection by atypical mycobacteria which can cause manifestations similar to TB.

Atypical mycobacterial species include: M. serofulaceum, M.intracellulare and M. fortuitum. They can simulate tuberculous infections and occur more frequently in immunocompromised patients e.g. with HIV infection (AIDS).

Investigations

TB diagnosis requires microbiological isolation (smear or culture of sputum, pus, CSF, urine, biopsy tissue) or histopathological documentation of the infection (caseating granuloma on biopsy)

1. Radiology: CXR or CT chest: classically shows upper lobe infiltrates with cavitation.

- It may be associated with hilar or paratracheal lymphadenopathy,

- Or may show changes consistent with prior TB infection, with fibrous scar tissue and calcification.

- Radiological presentation of TB in patients with AIDS or diabetic patients may be atypical.

- All patients with non-pulmonary TB should have a CXR to exclude or confirm pulmonary disease high resolution CT scan of the chest (HRCT) can be also used for diagnosis of TB.

2. Lab tests:

- Elevated inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP).

- Complete blood picture: in acute miliary TB, there may be a Leukoamid reaction or thrombocytopenia secondary to be bone marrow infiltration by TB.

- Serum electrolytes: (Na+ and K+) may show abnormalities (hyponatremia and hyperkalemia) in miliary TB secondary to suprarenal affection. In the latter condition, cortisol level is low.

- Adenosine deaminase {ADA) level > 40 U/ml in pleural effusion can be used for diagnosis of tuberculous pleural effusion.

3. Immunological tests:

Tuberculin skin test (TST):

- Cell-mediated immunity which is influenced by the T-lymphocytes. (N.B: CD4 is the T-helper lymphocytes and CDs is the T-suppressor lymphocytes).

- After 4-8 weeks from the initial infection, a cell-mediated i.e, delayed (type IV) hypersensitivity reaction to the (tuberculo protein) is developed. It is demonstrated by intradermal injection of such protein.

- Purified protein derivative (PPD) is injected intradermally, and the area of induration that forms as a cell mediated response is measured after 48-72 hours.

- Previous BCG vaccination can give a positive TST result.

False negative TST can occur in cases of: viral infections (measles), bacterial infections (typhoid), fungal infection, renal failure, lymphoma, sarcoidosis, use of corticosteroids, immunocompromisation, extremes of age, severe TB infection (acute miliary TB), and skin anergy.

Factors related to the tuberculin test can lead to a false negative test e.g. chemical denaturation of the fresh tuberculin, improper storage, and injection subcutaneously instead of intradermally.

Lastly, it should be noted that less than five percent of individuals with bacteriological proven pulmonary TB may present with negative tuberculin tests.

Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA): detects the level of Interferon-gamma (IFN-y) released by T-cells in response to MTB antigens. 2 blood tests for the IGRA are commercially available (QuantiFERON-TB Gold test and T-SPOT TB test).

4. Microbiological diagnosis:

Smear: Specimens are stained by the Ziehl-Neelsen method and visualized by direct microscopy. Specimens can be expectorated sputum, induced sputum by hypertonic saline nebulization, or gastric aspirate (in children). bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), CSF, or pleural effusion. For sputum samples, diagnosis of TB requires 3 successive positive smears.

Culture: It is considered the gold standard for microbiological diagnosis; however, it is time-consuming. Culture on conventional media (Lowenstein-Jensen medium) takes at least 6 weeks. The newer culture system (MGIT-Bactec system) takes 7 to 21 days (average of 2 weeks) for positive results.

Other rapid cultures are: Bactec-system which is a radiometric method using radioactive carbon (C14) in liquid media. Bacteriological cultures can be done with or without sensitivity testing for anti-TB drugs.

Nuclear acid amplification techniques:

Gene Xpert MTB/RIF assay: can simultaneously detect MTB and identify rifampicin resistance (which is strongly associated with MDR-TB) within 2h and has been recommended by the WHO for use in regions with high rates of HIV/TB co-infection or MDR-TB.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): This technique is capable of detecting one AFB/ml. It involves amplification of a single molecule of DNA. of the tubercle bacilli within a few hours to obtain millions of copies of the DAN of the TB bacilli.

5. Bronchoscopy: can be used to acquire bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or lymph node tissue (by endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)) for microbiological or histopathological diagnosis.

Chapter 4: Tuberculosis

Treatment Strategy

- Multidrug regimens are indicated for all cases of active disease.

- DOT (directly observed therapy) is the one recommended by the WHO for the treatment of TB.

- Start treatment with 4 drugs HRZE or HRZS (Isoniazid, Rifampicin, Pyrazinamide, Ethambutol or Streptomycin) for 2 months then continue with HR (Isoniazid and Rifampicin) for another 4 months.

- In some cases, the regimen is extended for 9 months.

- The regimen should be adjusted according to drug sensitivity.

- Monitoring of the liver enzymes, blood count, and visual disturbances is important during the course of treatment.

Drug Resistance

- Patients who do not have a favorable bacteriologic response early during treatment present a difficult problem.

- Drug resistance may be primarily due to infection by the organism which is resistant to drugs.

- Or acquired resistance which occurs because of inadequate treatment or noncompliance by the patient.

- Drug resistance may be mono resistance to one drug or multi-drug resistance.

- Multidrug-resistant TB (MOR-TB): resistant to at least Isoniazid and Rifampicin.

- Extensively drug-resistant TB (XOR-TB): resistant to Isoniazid and Rifampicin plus any fluoroquinolone (e.g., Levofloxacin, Moxifloxacin) and at least one of the injectable 2nd line drugs (e.g., Kanamycin, Capreomycin, Amikacin).

Latent TB infection is

Defined as a positive skin test or IGRA, Showing MTB infection but with a normal CXR and no symptoms. This represents the presence of a small total number of mycobacterial with a good host immune system. It should be distinguished from active disease which is usually accompanied by symptoms and an abnormal CXR

Vaccination

- BCG has been given to more persons (between 3 and 5 billion) than any other vaccine.

- In EGYPT, it is part of the expanded program of immunization given to all children in the first 3 months of age.

- BCG does not protect against TB infection but decreases the incidence of most serious forms like military TB and TB meningitis.

You can subscribe to Science Online on YouTube from this link: Science Online

You can download Science Online application on Google Play from this link: Science Online Apps on Google Play

Inflammation of the lung parenchyma, What causes lung parenchyma?, Is lung parenchyma dangerous

Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia Symptoms and Treatment, What is the difference between HAP and VAP?

Pneumonia causes, types, treatment, Is pneumonia usually serious? and Is pneumonia contagious?

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases Treatment, Types and Causes of COPD

Steps of Asthma Control, What is good control of asthma? and What is asthma management?

Spirometry uses, What is a normal spirometry level? and What is FEV1 in spirometry?

Lung structure, borders, Lobes, Fissures, and Broncho-pulmonary segments

Larynx structure, function, cartilage, muscles, blood supply, and vocal folds

Anatomy of the nose, function of para-nasal air sinuses, and Sphenopalatine Ganglion branches

Thoracic vertebrae structure, function, Chest wall muscles, and Intercostal arteries

Diaphragm anatomy, structure, function, Phrenic nerves, and Nerves of the thorax