Prevention of Recurrent Variceal bleeding, Gastric Varices and How do you stop variceal bleeding?

Variceal bleeding is a serious complication of liver disease, specifically cirrhosis. Preventing recurrent bleeding is crucial to improve patient outcomes and survival. The primary goal of preventing recurrent variceal bleeding is to reduce pressure in the portal vein.

Prevention of Recurrent Variceal Bleeding

Before diving into prevention, it’s essential to understand the root cause. Varices are abnormal, enlarged veins that develop in the esophagus and stomach. They form as a result of increased pressure in the portal vein, which is the main blood vessel carrying blood from the intestines to the liver. This increased pressure, often caused by liver damage, can lead to variceal rupture and bleeding.

Medical Management

- Beta-blockers help reduce blood pressure in the portal vein, decreasing the risk of variceal bleeding.

- Vasopressin and Terlipressin can be used to temporarily control active bleeding but are not recommended for long-term prevention.

- Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) involves placing rubber bands around varices to prevent bleeding.

- Sclerotherapy involves injecting a chemical into varices to cause them to harden and shrink.

In severe cases of liver disease, liver transplantation may be the ultimate treatment. Maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding alcohol, and following a balanced diet can help manage liver disease and reduce the risk of variceal bleeding. Patients with a history of variceal bleeding require close monitoring. Regular endoscopies and blood tests help assess the condition of the varices and liver function. Early detection of complications can allow for timely intervention.

Classification of Gastric Varices

- Gastroesophageal Varices (GOV): Lesser curve (GOV 1), Greater curve (GOV 2).

- Isolated Gastric Varices (IGV): Fundal (IGV1): Type I Junctional, Type II Fundal, Type III Linear.

- Rare varices: Antral, Duodenal, and Rectal.

Treatment of Gastric Varices

What is peculiar?

- Pharmacologic Rx can stop active bleeding.

- B-blockers may reduce the risk of recurrent hemorrhage.

- EST: Ulceration without variceal obliteration.

What is peculiar?

- Isolated gastric varices may occur in éplenic vein thrombosis resulting from pancreatitis, trauma, or other causes.

- Splenectomy is the treatment of choice in this setting and is typically curative.

Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy (PHG)

- Bleeding from PHG: Occult, Acute hemorrhage (rare).

- Percentage of patients bleeding from PHG at 1 year: 35% on Propranolol, 62% on Placebo.

Treatment of PHG

- Portal decompression: Portocaval shunt surgery, TIPS.

- APC-Argon Plasma Coagulation.

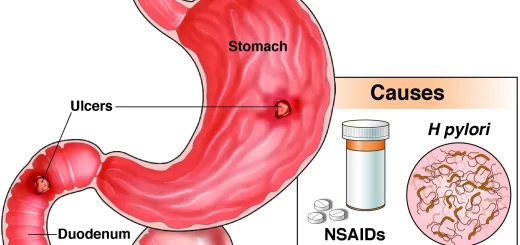

Non-Variceal Upper GI Bleeding

- PUD.

- GERD.

- Tumors.

- Mallorey Weiss tear

- AV malformation.

- Dieulafoy’s Lesion.

Acute management of severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- Resuscitation and stabilization, initiation of medical therapy with an intravenous proton pump inhibitor

- Assessment of onset and severity of bleeding.

- Risk stratification using a validated prognostic scale

- Diagnostic endoscopy: Preparation for emergent upper endoscopy, Localization and identification of the bleeding site, Identification of stigmata of recent hemorrhage, Stratification of the risk for rebleeding

- Therapeutic endoscopy: Control of active bleeding or high-risk lesions/Minimization of treatment-related complications/Treatment of persistent or recurrent bleeding.

Treatment of Bleeding Ulcer

Endoscopic Methods: Heater Probe, Coagulation (Monopolar or Bipolar), Sclerotherapy, Band Ligation, APC, Laser Therapy.

Summary of consensus recommendations for the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal gastrointestinal bleeding:

- Resuscitation, risk assessment, and pre-endoscopy management Immediately evaluate and initiate appropriate resuscitation.

- Prognostic scales are recommended for early stratification of patients into low-and high-risk categories for rebleeding and mortality.

- Consider the placement of a nasogastric tube in selected patients because the findings may have prognostic value.

- Blood transfusions should be administered to a patient with a hemoglobin level less than or equal 7g/L.

- In patients receiving anticoagulants, correction of coagulopathy is recommended but should not delay endoscopy.

- Promotility agents should not be used routinely before endoscopy to increase the diagnostic yield.

- Selected patients with acute ulcer bleeding who are at low risk for rebleeding based on clinical and endoscopic criteria may be discharged promptly after endoscopy.

- Pre-endoscopic PPI therapy may be considered to downstage the endoscopic lesion and decrease the need for endoscopic intervention but should not delay endoscopy.

Endoscopic management

- Develop institution-specific protocols for multidisciplinary.

- management. (Include access to an endoscopist trained in endoscopic hemostasis.)

- Have available on an urgent basis support staff trained to assist in endoscopy.

- Early endoscopy (within 24 hours of presentation) is recommended for most patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Endoscopic hemostatic therapy is not t indicated for patients with low-risk stigmata (a dean-based ulcer or a nonprotuberant pigmented dot in an ulcer bed).

- A finding of a dot in an ulcer bed warrants targeted irrigation in an attempt at dislodgement, with appropriate treatment of the underlying lesion.

- The role of endoscopic therapy for ulcers with adherent dots is controversial. Endoscopic therapy may be considered, although intensive PPI therapy alone may be sufficient.

- Endoscopic hemostatic therapy is indicated for patients with high-risk stigmata (active bleeding or a visible vessel in an ulcer bed).

- Epinephrine injection alone provides suboptimal efficacy and should be used in combination with another method.

- No single method of endoscopic thermal coaptive therapy is superior to another.

- Clips, thermocoagulation, or sclerosant injection should be used in patients with high-risk lesions, alone or in combination with epinephrine injection.

- Routine second-look endoscopy is not recommended.

- A second attempt at endoscopic therapy is generally recommended in cases of rebleeding.

Pharmacologic management

- Histamine-2 receptor antagonists are not recommended for patients with acute ulcer bleeding.

- Somatostatin and octreotide are not routinely recommended for patients with acute ulcer bleeding.

- An intravenous bolus followed by continuous-infusion PPI therapy should be used to decrease rebleeding and mortality in patients with high-risk stigmata who have undergone successful endoscopic therapy.

- Patients should be discharged with a prescription for a single daily dose of oral PPI for a duration as dictated by the underlying etiology.

Non-endoscopic and nonpharmacologic in-hospital management

- Patients at low risk after endoscopy can be fed within 24 hours.

- Most patients who have undergone endoscopic hemostasis for high-risk stigmata should be hospitalized for at least 72 hours thereafter.

- Seek surgical consultation for patients for whom endoscopic therapy has failed.

- Where available, percutaneous embolization can be considered as an alternative to surgery for patients for whom n endoscopic therapy has failed.

- Patients with bleeding peptic ulcers should be tested for H. pylori and receive eradication therapy if it is present, with confirmation of eradication.

- Negative H. pylori diagnostic tests obtained in the acute setting should be repeated.

Post-discharge, ASA, and NSAIDS

- In patients with previous ulcer bleeding who require an NSAID, it should be recognized that treatment with a traditional. NSAID plus PPI or a COX-2 inhibitor alone is still associated with a clinically important risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding,

- In patients with previous ulcer bleeding who require an NSAID, the combination of a PPI and a COX-2 inhibitor is recommended to reduce the risk for recurrent bleeding from that of Cox-2 inhibitors alone.

- In patients who receive low-dose ASA and develop acute ulcer bleeding, ASA therapy should be restarted as soon as the risk for cardiovascular complication is thought to outweigh the risk of bleeding.

- In patients with previous ulcer bleeding who require cardiovascular prophylaxis, it should be recognized that clopidogrel alone has a higher risk for rebleeding than ASA combined with a PPI.

Rapid overview: Emergency management of severe upper GI bleeding

- Major causes.

- Peptic ulcer,

- esophagogastric varices.

- arteriovenous malformation,

- tumor,

- esophageal (Mallory-Weiss) tear.

Clinical features

History

- Use of: NSAIDs aspirin, anticoagulants, and antiplatelet agents.

- Alcohol abuse previous GI bleeding; liver disease; coagulopathy.

- Symptoms and signs: abdominal pain; hematemesis or coffee ground” emesis; passing melena/tarry stool (stool may be frankly bloody or maroon with massive or brisk upper Gl bleeding).

Examination

- Tachycardia and orthostatic blood pressure changes suggest moderate to severe blood loss; hypotension life-threatening blood loss (hypotension may be late finding in healthy younger adults).

- Rectal examination is performed to assess stool color (melena vs. hematochezia vs. brown) and perform guaiac testing.

- Significant abdominal tenderness accompanied by signs of peritoneal irritation (e.g., involuntary guarding) suggests perforation.

Diagnostic testing

- Obtain type and screen (or type and crossmatch for hemodynamic instability, severe bleeding, or high-risk patient).

- Obtain hemoglobin concentration (normal measurement may be inaccurate with acute severe hemorrhage), platelet count, coagulation studies (prothrombin time with INR), liver enzymes (AST, ALT), albumin, BUN, and creatinine

- Nasogastríc lavage may be helpful if the source of bleeding is unclear (upper or lower GI tract) or to clean the stomach before endoscopy.

Treatment

Closely monitor the airway, clinical status, vital signs, cardiac rhythm, urine output, and nasogastric output (if the nasogastric tube is in place). DO NOT give the patient anything by mouth. Establish two large bore IV lines (16 gauge or larger). Provide supplemental oxygen. Treat hypotension initially with rapid, bolus infusions of isotonic crystalloid.

Transfuse for:

- Hemodynamic instability despite crystalloid r resuscitation.

- Hemoglobin <10 g/dL (100 g/L) in high-risk patients (e.g., elderly, coronary artery disease).

- Hematocrit 7 g/dL (70 8/L) in low-risk patients.

- Avoid over-transfusion with possible variceal bleeding Give fresh frozen plasma for coagulopathy.

- give platelets for thrombocytopenia (platelets c50,000) or platelet dysfunction (e.g chronic aspirin therapy).

Obtain immediate consultation with a gastroenterologist; obtain surgical and interventional radiology consultation for any large-scale bleeding. Pharmacotherapy for all patients with suspected or known severe bleeding: Give a proton pump inhibitor (e.g., Esomeprazole 30 mg av bolus, followed by 8 mg/hour OR Pantoprazole 30 mg IV bolus, followed by 3 mg/hour infusion).

Pharmacotherapy for known or suspected esophagogastric variceal bleeding and/or cirrhosis: Give somatostatin or an analogue (e.g. octreotide 50 mcg bolus, followed by 50 mcg/hour infusion). Give an antibiotic (e.g., Ceftriaxone, Amoxicillin-clavulanate, or Quinolone).

Balloon tamponade may be performed as a temporizing measure for patients with uncontrollable hemorrhage likely due to varices using any of several devices (e.g., Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, Minnesota tube); tracheal intubation is necessary if such a device is to be placed; ensure proper device placement before inflation to avoid esophageal rupture

Lower GI bleeding

Causes of lower Gl bleeding

- Anatomical: Diverticulosis.

- Vascular: Angiodysplasia, Radiation-induced telangiectasia.

- Inflammatory: Infectious, Ischemic, Idiopathic IBD, Radiation.

- Neoplastic: Polyp, Carcinoma.

- Others: Hemorrhoids, Ulcer, Post biopsy or Polypectomy.

Methods of Diagnosis

- Colonoscopy.

- Radionuclide Scanning.

- Angiography.

Endoscopic methods of Rx

- Heater probe.

- Coagulation.

- Laser.

- ABC.

- Band Ligation.

- Loops.

- Clips.

Occult GI Bleeding

Evaluation of occult GI bleeding: Incidental finding > > Fe deficiency anemia/FOB.

- Occult positive Stools (EOBT).

- Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA).

Obscure GI Bleeding

- Bleeding from the GI tract that persists or recurs without an obvious etiology after EGD, Colonoscopy &/or, Radiologic evaluation of the small bowel e.g., small bowel follow-through or enteroclysis.

- Obscure Occult: FOBT, IDA.

- Obscure Overt: Recurrent Visible Bleeding.

Etiology of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding

Upper GI and lower Gl bleeding overlooked:

- Upper GI lesions.

- Cameron’s erosions.

- Fundic varices.

- Peptic ulcer.

- Angioectasia.

- Dieulafoy’s lesion.

- Gastric antral vascular ectasia.

Lower GI lesions:

- Angioectasia.

- Neoplasms.

Mid-GI bleeding

- Younger than 40 years of age: Tumors, Meckel’s diverticulum, Dieulafoy’s lesion, Crohn’s disease, and Celiac disease.

- older than 40 years of age: Angioectasia, NSAID enteropathy, and Celiac disease.

Uncommon

- Haemobilia.

- Hemosuccus pancreaticus.

- Aortoenteric fistula.

Capsule Endoscopy

- A-V Malformation.

- Crohn’s Disease of the small intestine.

You can subscribe to Science Online on YouTube from this link: Science Online

You can download Science online application on Google Play from this link: Science online Apps on Google Play

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) cause, treatment, and How to treat eosinophilic esophagitis?

Pharynx function, anatomy, location, muscles, structure, and Esophagus parts

Tongue function, anatomy and structure, Types of lingual papillae, and Types of cells in taste bud

Mouth Cavity divisions, anatomy, function, muscles, Contents of Soft palate and Hard palate

Temporal and infratemporal fossae contents, Muscles of mastication and Otic ganglion

Stomach Cancer (Gastric Adenocarcinoma) Symptoms, Causes and Treatment